Hurricane Katrina: 10 Years after the Storm

It’s been a decade since Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. In that time, we’ve examined almost every aspect of federal recovery efforts following the storm. Today, we look back at some of that work and explore how to reduce the costs of future disasters.

Keeping a pulse on health care

Within months of Hurricane Katrina striking the Louisiana-Mississippi coast, we were on the ground assessing New Orleans' health care system. Over the next several years, we reported on numerous topics, including hospital and nursing home evacuation and shortcomings in federal evacuation assistance. We reported in 2006, for example, that federal help for evacuating hospital patients wasn’t set up to deal with nursing homes. The Department of Health and Human Services took multiple steps to address our recommendations for assisting nursing home residents, such as contracting with ground and air ambulances in hurricane-prone regions.

Rebuilding education

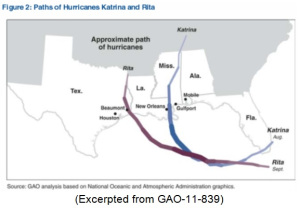

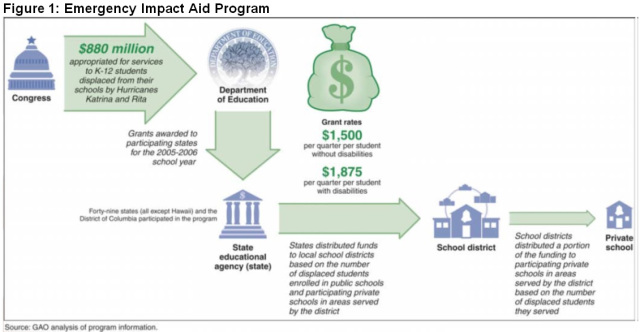

To help students continue their education after losing their homes or schools to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Congress appropriated over $800 million in Emergency Impact Aid.

(Excerpted from GAO-11-839)

(Excerpted from GAO-11-839)

While some states and districts told us for our 2011 report that they were generally pleased with the support provided by the Department of Education, others didn’t think the assistance was enough. In addition, other districts had to return funds when, for example, they couldn’t accurately count the number of displaced students in their schools.

Helping survivors

A few years after Katrina, we examined federal assistance offered to several thousand Katrina survivors still living in FEMA-provided trailers who needed help with permanent housing, jobs, transportation, and other services. We found that federal aid efforts were hampered not only by the level of destruction, which made it difficult to place temporary housing near supermarkets and services, but also by a lack of information about the people needing help.

Getting transit agencies back on track

Major storms can cause major disruptions to transit by destroying buses, disrupting routes, and otherwise derailing operations. After the 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes, FEMA and the Federal Transit Administration faced challenges providing timely and effective assistance to transit agencies. For example, FEMA took up to 4 months to decide what types of transit services to fund, in part because officials lacked guidance.

In 2008, we made recommendations, including to clarify what types of assistance FEMA will or will not fund following disasters. As a result, the federal government may now be in a better position to provide immediate post-disaster transit assistance.

Alerting the public

During an emergency, information is critical. In 2004, FEMA started work on a nationwide emergency public alert system. While other systems existed, this one was intended to integrate federal and state alerts into a single system to more efficiently notify the public, including by TV, radio, and text message.

Despite improvements in the system’s capabilities, a nationwide test identified problems, and state and local officials told us of challenges in testing and implementing the system. In 2013, we made recommendations to improve the testing of the nationwide system. We will follow FEMA’s progress to help ensure this important system functions as intended.

Planning for extreme weather events

Looking ahead, some agencies have begun considering how to minimize damage from extreme weather events. For example, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recently issued guidance on evaluating the effects of projected sea-level changes on its dams, levees, and other water-resource infrastructure projects. However, as we reported in July, the Corps isn’t required to perform systematic, national risk assessments on other types of infrastructure, such as hurricane barriers and floodwalls, nor has it done so.

Reducing costs

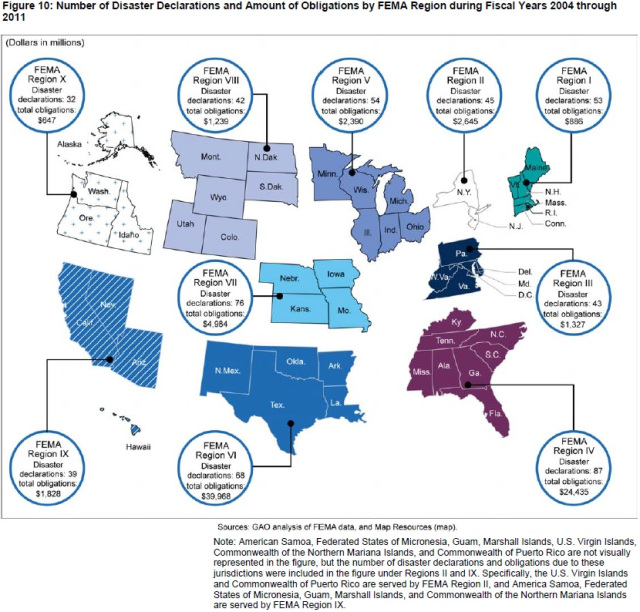

The nation is spending more federal dollars on natural disasters. When a president declares a major disaster, that triggers federal spending that flows to states, local governments, households, individuals, and more. From fiscal years 2004 to 2011, presidents declared 539 major disasters for which FEMA obligated more than $80 billion—roughly half for Hurricane Katrina alone.

(Excerpted from GAO-12-838)

(Excerpted from GAO-12-838)

We’ve made multiple recommendations on ways to save money. For example, in 2012 we recommended reducing FEMA’s rising administrative costs and improving the way it determines whether a state needs federal assistance to recover from a major disaster.

We also continue to encourage federal efforts to help the nation prepare for, recover from, and adapt to future disasters. As we again reported in 2015, “disaster resilience and hazard mitigation” could help limit the costs of recovering from disasters. Listen to Chris Currie, a director in GAO’s Homeland Security and Justice team, explain:

- Questions on the content of this post?

- For health care, contact Linda Kohn at kohnl@gao.gov.

- For education, contact Charles Jeszeck at jeszeckc@gao.gov.

- For federal aid to survivors, transit, and alerting the public, contact Mark Goldstein at goldsteinm@gao.gov.

- For planning for extreme weather events, contact Anne-Marie Fennell at fennella@gao.gov.

- For reducing costs, contact Chris Currie at curriec@gao.gov.

- Comments on the GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact blog@gao.gov.