COVID-19 Exposure Notification Apps Are Available. But Are They Working?

As COVID-19 cases continue to surge, manual contact tracing—tracking the spread of the virus from person to person—has been cited as one way to mitigate the spread of the virus. To supplement manual contact tracing, public health authorities (both in the United States and internationally) have deployed exposure notification apps that can be downloaded by smartphone users.

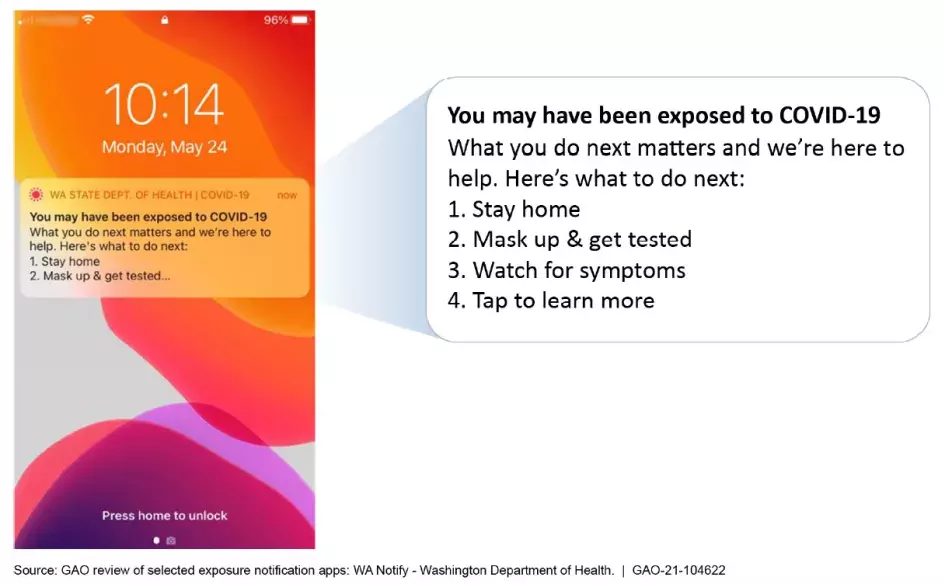

The apps are intended to detect when 2 app users are in close contact, then send a notification if 1 of them later tests positive for COVID-19. But how widely are these apps being used and what challenges do they present?

In today’s WatchBlog post, we explore our new report on exposure notification technology and what it means for the future.

Example of an exposure notification message

Image

Are exposure notification apps working?

Researchers and state officials say these apps are functioning as intended, meaning they are notifying people about potential exposure to COVID-19. Where it gets complicated is proving that those notifications result in people staying home or getting tested, and that those actions then slow the spread of COVID-19.

Early studies made assumptions about how people would behave—such as the likelihood that they would use the app, or that they would self-isolate after receiving an exposure notification. There simply was not data on how people behave during a pandemic. Now, new studies are starting to emerge that are based on use of the apps following their deployment. Some of the studies show promising results, but it’s still too early to say just how effective the apps are

Are enough people using these apps to make them effective?

For our recently completed review, we looked at how 11 states used exposure notification apps—Alabama, Colorado, Connecticut, Louisiana, Minnesota, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Utah, Virginia, and Washington. Officials from these states said adoption rates ranged from 19% to 49%. But these numbers are not apples-to-apples comparisons.

For example, some states reported the percentage of the total population while others reported an estimated percentage of smartphone owners. And in most cases, states are measuring downloads to determine adoption rates, which would not tell them the portion of those who actually use the apps consistently. Some users are also not reporting if they test positive or taking precautions if exposed.

Why might adoption vary across states?

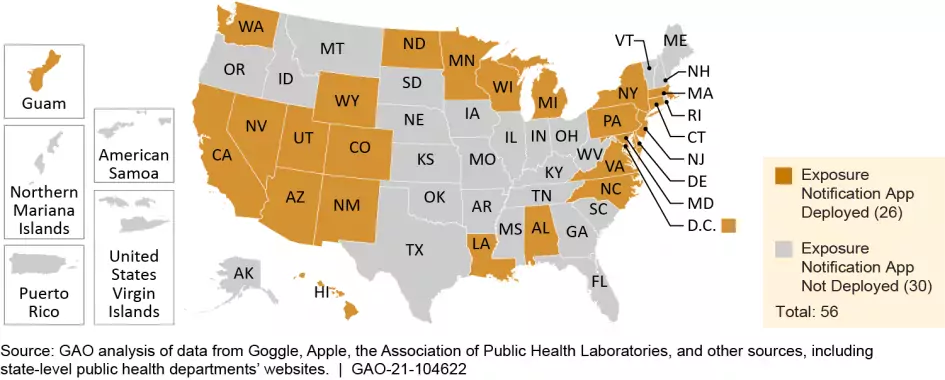

One reason for variation is that states adopted exposure notification apps at different times or not at all. We found that 26 states deployed apps over a span of 10 months, in a staggered rollout beginning in August 2020. Virginia was the first state to deploy an exposure notification app, in August 2020, and Massachusetts was the most recent, in June 2021. Officials from 7 of the states in our review that had not deployed an app cited several reasons for that decision, including limited cell phone coverage in rural areas, or competing priorities, such as vaccine distribution efforts.

Map of exposure notification app deployment by U.S. states and territories, as of June 2021

Image

We also found app marketing and promotion efforts varied across the states we interviewed for our report. State officials also said privacy concerns were a common barrier to adoption, despite the fact that user privacy and security were priorities in designing the apps. For instance, these apps are designed so that states do not know who has downloaded the app, who has been in contact with whom, or who has received exposure notifications.

Notifications from apps are also anonymous, which means your app won’t tell you from whom you got COVID-19. Further, these apps do not collect data on a user’s location or with whom they’ve been in contact. Also, even after testing positive, you need to volunteer to submit that information to enable the anonymous notification.

But while app developers took privacy into consideration, we’ve proposed a couple different options for policymakers to consider that might improve adoption. For instance, we reported that policymakers could promote uniform privacy and security standards for these apps. Or they could incorporate the apps into the national COVID strategy, potentially paving the way for more coordinated app deployment in the future.

Why do exposure notification apps still matter more than a year and half into the pandemic?

With the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, new variants, and some vaccinated people getting sick, contact tracing still continues to play an important role. There are no plans to discontinue their use anytime soon, particularly as vaccinated and unvaccinated people intermingle, and with the emergence of more transmissible disease variants.

Beyond COVID-19, state and public health officials told us that exposure notification apps could potentially play an important role in preventing the spread of other infectious diseases (e.g., measles) or during potential future pandemics.

In the end, exposure notification apps function as intended. What’s less clear is whether or not they are effective in slowing the spread of COVID-19.

Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact blog@gao.gov.

GAO Contacts

Related Products

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to blog@gao.gov.