Border Security and Immigration

Issue Summary

The federal government is responsible for conducting a number of activities to protect U.S. borders and enforce immigration laws, mainly through the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ). However, there are a number of areas in which these agencies can improve how they manage and implement these activities, on which they spend billions of dollars each year.

For instance:

- Checkpoint data. DHS’s U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is responsible for securing U.S. borders at and between ports of entry. Within CBP, U.S. Border Patrol operates over 100 immigration checkpoints along U.S. borders where agents screen vehicles to identify noncitizens who are potentially removable; they may also enforce U.S. criminal law. Agents are required to collect data on checkpoint activity, including how many smuggled people are apprehended and how many drug seizures were made using canines. However, agents at checkpoints inconsistently documented this data, which makes oversight of these checkpoints difficult.

Border Patrol Checkpoint Canine Team Inspects a Vehicle

Image

- Incidents involving CBP personnel. CBP personnel may be involved in “critical” incidents that result in serious injury or death, such as a child dying in custody. They may also be involved in less serious, “noncritical” incidents, such as a vehicle accident that results in property damage. While CBP’s Office of Responsibility is to investigate critical incidents, Border Patrol sectors respond to noncritical incidents involving their agents and assess the agency’s liability for associated property damage. However, without guidance or oversight from headquarters, the sectors approach noncritical incident response inconsistently and there are concerns their activities may infringe on investigations of critical incidents.

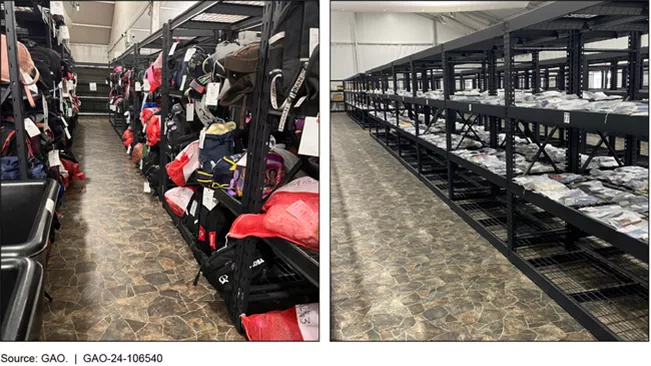

- Noncitizens' personal property. CBP may hold noncitizens in short-term custody in facilities along the southwest border. CBP is to collect their personal property, store it, and return it when they are released. CBP has guidance for handling personal property, but some of it is unclear— resulting in field locations interpreting it differently. For example, some locations discard property over a certain amount or size, while others don’t. Also, field locations' instructions for people to retrieve their personal property after release are inconsistent, and CBP doesn’t monitor how locations implement its guidance.

Property Storage Rooms at Two CBP Facilities

Image

- Immigration enforcement. DHS’s U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is responsible for immigration enforcement within the U.S. This includes making arrests, providing safe confinement of noncitizens in detention facilities, and removing noncitizens. Regarding detentions, ICE’s public reporting doesn’t include all people it detains in its facilities, resulting in underestimates of tens of thousands of people. For example, in FY 2022, ICE’s reporting excluded detentions of 136,706 individuals. ICE also doesn’t fully explain its methodology. As a result, Congress and the public may not have a complete understanding about how to interpret the data.

- Segregated housing. ICE made nearly 15,000 segregated housing placements—which is where individuals are in one or two-person cells separate from the general population—from FYs 2017-2021. ICE monitors segregated housing placements involving vulnerable persons—e.g., those with medical or mental health conditions. But it relies on reports and data that don't always have enough detail about the circumstances leading to a placement. As a result, ICE can't adequately oversee segregated housing.

- Alternatives to Detention. ICE is also responsible for monitoring noncitizens it releases into the community during their immigration court proceedings and has increasingly used its Alternatives to Detention program to do so. The program offers ICE options for monitoring people (e.g., GPS or home visits) to help ensure compliance with release requirements, such as appearing in court. ICE uses a $2.2 billion contract to administer this program, but it doesn't fully assess how the program is working or ensure that the contractor meets standards.

- Immigration fraud. DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) processes millions of applications and petitions for immigration benefits each year. USCIS also investigates potential immigration fraud. For example, USCIS investigates concerns that some marriages are formed to evade U.S. immigration law or illegally obtain immigration benefits, such as permanent residence. USCIS uses a staffing model to estimate how many immigration officers it needs for its antifraud workload. However, the model doesn't adequately reflect operating conditions. USCIS has also made a variety of changes to its antifraud activities, but it hasn’t evaluated their effectiveness or efficiency.

- Immigration reviews. The Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) conducts immigration court removal proceedings. At the start of FY 2023, EOIR had a backlog of about 1.8 million pending cases, which means that some individuals have been waiting years to have their cases heard. Continued implementation of workforce planning should help EOIR address its staffing needs and the case backlog.