Science & Tech Spotlight: Opioid Vaccines

Fast Facts

More than 10 million people in the United States abused opioids such as heroin and fentanyl in 2017, and there were over 47,000 opioid-related overdose deaths.

One treatment under development is an opioid vaccine, which could block the drugs from entering the central nervous system. It essentially immunizes patients from drug-induced euphoria, as well as addiction and overdose. Advantages of a vaccine over current treatments include a minimal need for medical supervision and no potential for abuse.

Clinical trials of opioid vaccines have begun, and additional research is ongoing.

File photo of a scientist uses a dropper to put liquid into a test tube

Highlights

The Technology

What is it? Opioid vaccines are medical therapies designed to block opioids, such as heroin and fentanyl, from entering the brain or spinal cord, thus preventing addiction and other negative effects. While none are approved for use yet, they could be useful for at-risk individuals, patients in drug recovery programs, or first responders who might accidentally come into contact with deadly opioids that can be absorbed through the skin. This approach offers advantages over some current treatment methods, including requiring minimal medical supervision and no potential for abuse.

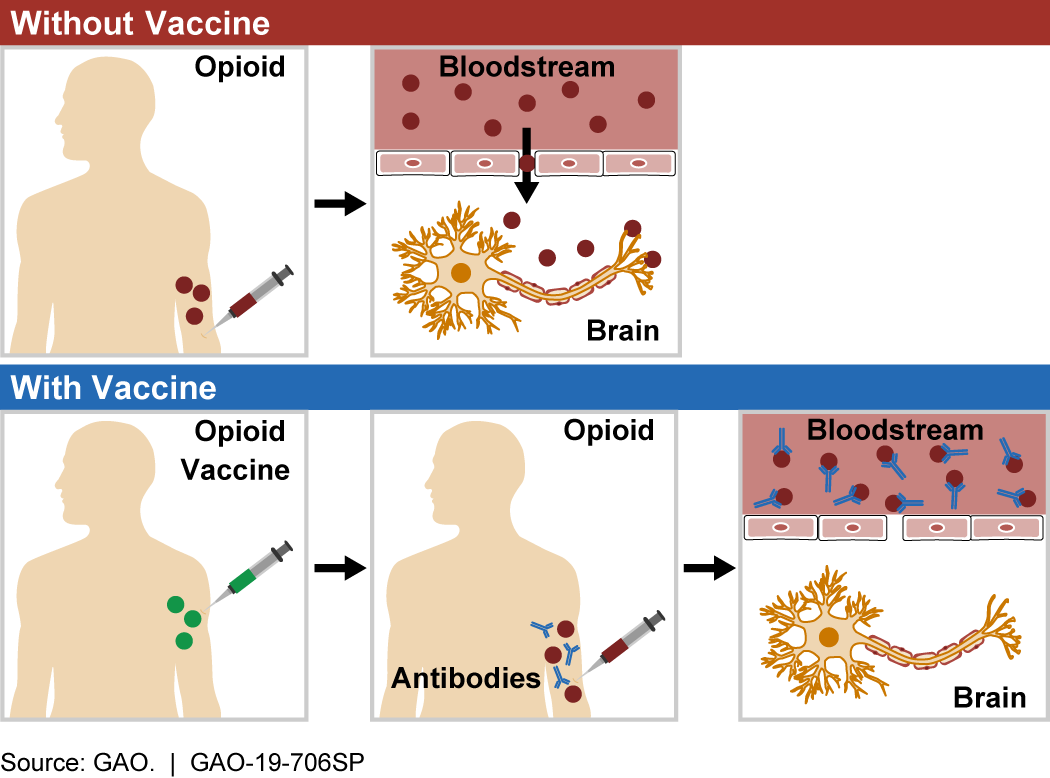

Figure 1. When an opioid enters the bloodstream (top), it crosses into the brain, where it can act on the target receptor to cause psychotropic effects, addiction, and overdose. Opioid vaccines (bottom) trigger the body to create antibodies that bind to opioid molecules and prevent them from entering the central nervous system, thus preventing negative effects.

How does it work? When opioid molecules bind to receptors in the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), they can cause psychotropic effects (e.g., hallucination, euphoria), addiction, and overdose. Opioid molecules have specific chemical structures. Opioid vaccines are designed to trigger an immune response to these structures when injected into a patient. Similar to vaccines for infectious diseases, such as polio or measles, when a patient is treated with an opioid vaccine, their immune system learns to identify the targeted opioid as a dangerous foreign substance so it can respond if that opioid enters the bloodstream in the future.

After the body has learned to target an opioid molecule, it naturally forms antibodies that can bind to it. These opioid-specific antibodies stick to opioid molecules in the bloodstream, forming a unit that is too large to enter the central nervous system. Without entering the central nervous system, the molecule is not able to produce the negative effects associated with opioids.

How mature is it? As of 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any opioid vaccines for use. While opioid vaccine studies were initially proposed as early as the 1970s, clinical trials have thus far been unsuccessful. Currently, at least three early-stage clinical trials of potential opioid vaccines are underway, including one that the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research is conducting on a heroin vaccine.

Opportunities

- Treat at-risk patients. Unlike some current treatment options, opioid vaccines do not carry the risk of abuse. This could allow for more effective treatment of patients at high risk of abusing another medication, such as methadone.

- Medical advantages. The vaccines have a long duration (months to years) of action and require limited medical supervision.

- Compatible with other therapies. Vaccines currently in development are targeted to illicit use of opioids such as heroin and fentanyl, and therefore do not interfere with most drug treatment or pain management therapies.

- Protection against accidental exposure. Vaccines could be administered prophylactically to individuals at risk of accidental exposure to opioids, such as law enforcement, military, and first responders.

Challenges

-

Lack of broad-based effect. Current opioid vaccines are designed against the specific chemical structure of each opioid; therefore, multiple vaccines would be needed to provide broad-spectrum immunity. In addition, opioids such as fentanyl can be easily altered into a series of similar molecules called analogs, further complicating vaccine development.

-

Less effective in immune-compromised patients. Patients with opioid use disorders often have other infections and altered immune responses that may limit the effectiveness of vaccines.

-

Mechanism not well understood. The current biological mechanism of opioid vaccines is not as well understood as that of vaccines for infectious diseases.

-

Patient consent. Consent issues could arise for people who might receive an opioid vaccine. For example, some might question a parent’s right to compel their child to take a vaccine against a non-infectious agent, or an addicted person’s ability to understand potential long-term effects of an opioid vaccine.

-

Interference with medical care. If vaccines were developed against legal opioids that are used for pain management, vaccinated individuals would have a reduced risk of addiction but would also be unable to use those medications as effective treatments.

-

Insurance and payment. Recent refusals to provide insurance to individuals who carry naloxone, used to counter opioid overdose, highlight the insurance issues surrounding opioid-related treatments. Would insurance cover an opioid vaccine? What might be the baseline costs?

Figure 2. Opioid vaccines will likely have a wide range of social and economic effects that could impact the individual.

Why This Matters

The ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States impacts lives on both a personal and national level. More than 10 million people abused opioids in 2017, with more than 47,000 opioid-related deaths—a nearly six-fold increase since 1999. Opioid vaccines could offer advantages over current treatment options.

Policy Context and Questions

-

What means are available to facilitate the development of successful commercial opioid vaccines?

-

What standards and validations should the FDA set for clinical trials of an opioid vaccine?

-

When and to whom should an opioid vaccine be administered?

-

What insurance coverage options are there for opioid vaccines?

For more information, contact Tim Persons at 202-512-6412 or personst@gao.gov.